Table of Contents

Point of Diminishing Returns

In microeconomics, the point of diminishing returns refers to the optimal level of capacity, which is the inflection point of a return or production function. The point of diminishing returns defines a threshold after which even though production might increase, the returns for the additional production will not increase but rather will diminish if the factors of production are held constant.

The point of diminishing returns is brought up sometimes in order to counter the misheld belief that growth is exponential under the constraints that the production factors remain the same. A parallel could be drawn to the automotive industry where one could assume that at a certain point in time, there would be at least one car per capita such that even if the automotive industry would increase production, the cars could not be sold or very few cars would be sold compared to the increase in production since everyone would already own a car.

One solution to the point of diminishing returns as well as a frequent choice for enterprises is to diversify the production thereby changing the factors of production and resolving the problem. For instance, following the example mentioned before, an automotive industry might try to enter other markets, unrelated to the automotive industry and thereby diversify its production catering to different needs.

The Minimum Wage

- [Austrian School of Economics] In short, raising the minimum wage can deter employers from hiring staff iff. the staff being hired cannot produce more in terms of revenue for the employer than the value of the minimum wage that an employer would be forced to pay due to the minimum wage.

- The result could be the diminishing of the available jobs since employers would become protective due to the increased risk of maintaining staff.

Universal Basic Income

The Universal Basic Income (UBI) can be summarized as the implementation of a state provided wage for everyone regardless whether they are working or not working.

Causes of The Great Depression

As explained by Robert P. Murphy on behalf of mises.org:

Possible Views

- unregulated markets leading to margin trading and speculation of stocks,

- same principle behind the recent housing crisis,

- bubble, crash and the misery continued due to Herbert Hoover not intervening believing that it is best to not interfere with markets,

- due to FDR's "New Deal", wide-range of economic intervention from government, in contrast to the arrangement of Herbert Hoover,

- World War 2 solved the depression, due to government spending

Keynesianism

- Hoover and FDR implemented contractionary policy by reducing government spending that ultimately led to the lingering of the crisis (instead of supposed to do the opposite and increase government spending),

- interest rates pushed so low that the federal reserve could not intervene such that the government should have started running a budget deficit,

- private debt overhang preventing creditor spending since collectively individuals start to save more and thereby will decrease the overall spending,

- pushes down income to the point where people save less than they originally intended to save,

- World War 2 deficit spending ended the depression,

- argues that the impeding threat convinced a formerly shy government to run a higher budget deficit

The Monetary Position (Chicago School)

- Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz blame the federal reserve for not inflating enough; the fed should have pumped more money into the economy to compensate for the bank run trend instead of letting the banks fail,

- contrary to views where government intervention caused the issue,

- low interest rates are a symptom of money being too tight,

- it is insufficient to look at interest rates and a mistake of Keynesian economics,

- in the 20s, when the market started to tank, the government intervened due to historical factors where the fed failed to come to the rescue again and inflate the market; the fed should have continued to stimulate the market

Murray Rothbard, Mises and Hayeck (Austrian School)

- the Austrian school considers that impulsively acting on the effect rather than the cause could just possibly sow the seeds of the next boom and bust cycle,

- analyzing the unsustainable boom instead of blaming the bust, the bust acting as just an awakening but ultimately cannot be blamed since it is a consequence,

- traditionally economists look at the effect (the bust) rather than the cause (the boom) and should not do so,

- contrary to the monetarists such as Friedman, the argument given is that the federal reserve intervened one too many times just to keep the boom going,

- unprecedented intervention on behalf of Hoover resulted in turning a small depression into a large depression,

- if the economy would have been left to crash, then the misery would not have been prolonged due to the economy having no other direction to go after a crash but up,

- certain lines or avenues of production expanded too quickly instead of accounting for potential future complementary demand,

Fractional Reserve Banking

Born from the The Glass-Steagall Act, an ulterior deregulations lowered the requirement of banks to back up money put in circulation with reserves. Historically speaking, banks had to cover assets in circulation with reserves, typically in gold and that would ensure that if all bank clients requested the money at a certain point in time, the bank had enough to cover the demand. The removal of such regulation, and allowing the banks to run on fractional reserves, is thought by many to be a stimulus to the economy and to bolster economic growth by allowing banks to create money in turn. Unfortunately, fractional reserve banking is susceptible to bank runs where in times of crisises, clients turn to the banks to retrieve large amounts of assets out of fears of stability that, due to the bank not having sufficient assets on hand to pay off the customers, results in the banks crashing or the government having to intervene thereby increasing inflation in turn.

The Risks of Deflation vs. Inflation (Monetarism)

Deflation (currency appreciation):

- currency appreciation leads to a stagnation of markets due to players tending to hoard the currency due to its increased value,

Inflation (currency depreciation):

- currency depreciation leads to players attempting to dump the currency, in favor of alternate transactional assets (ie: other currencies), due to its decreased buying power,

Collection of Arguments against the Bitcoin Currency

- is a deflationary currency meaning that players will hoard the currency and will be reluctant to trade in the currency due to its ever-increasing value; since the value of bitcoin will by design only increase, there is more of an incentive to hold onto the currency than use the currency to make purchases,

- bitcoin has a very weak transactional value due to its usability being limited to a very small sector of the market; historically speaking, used to buy black-market stolen goods, drugs and weapons,

- as the value of the currency increases, the investment required to mine the same amount increases such that at some point a cross-over (point of diminishing returns) will be reached where mining will require more money than the yields resulting from the mining,

- even though bitcoin claims to be anonymous, the moment that bitcoin is converted into a currency of global circulation, de-anonymization occurs and the money is simply traced to the beneficiary; assuming that the beneficiary is fair (and that the market needs the beneficiary to convert bitcoin into some other currency), then the beneficiary would be subject to taxation just like any other currency.

Pyramid Schemes

A pyramid scheme is a fraudulent system of making money based on recruiting an ever-increasing number of investors that bring fresh money into the game. Pyramid schemes are by default spirals that have the tendency of amplifying themselves over time and in width depending on the number of participants.

Examples

- some companies, for instance, beauty product companies, recruiting people to advertise and distribute products on the basis that the number of sales and the number of people recruited are directly related to the rewards given by the company

Earth's Ice Caps

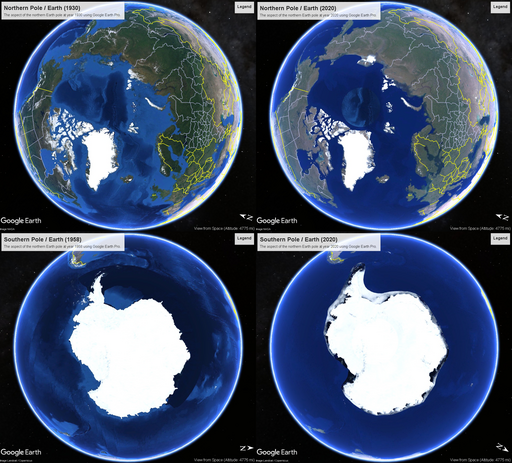

One of the popular thesis is that the Earth's ice caps, in particular the northern ice cap, have melted over time and that the situation will pose an existential threat in the future to the planet's survival.

Using publicly available data, such as Google data via the Google Earth Pro application, and looking back in time (say, approximately in the year 1930), it is observable that the ice around the northern pole of the Earth is way more spread out than the ice around the north pole in year 2020.

One of the interesting things however, is that if you look at the southern ice cap, and perform the same operation; check the oldest recording and compare to the most recent one, it seems that the ice has remained at the same amount in 1958 and then in 2020.

Given that the northern hemisphere population is 6.96 billion people (87.0% of the Earth's total human population) and the southern hemisphere population is 1.04 billion people (13% of the population) it might be the case that the melting of the northern ice cap could be attributed to the population difference between the northern, respectively southern hemisphere.

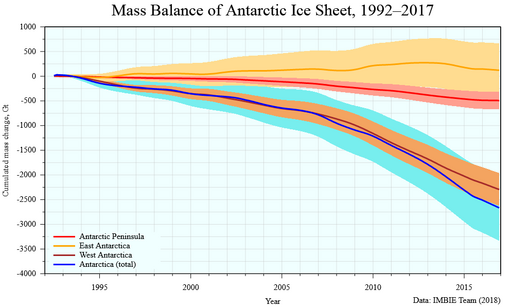

In fact, looking at the antarctic ice quantity over time, even for short time periods such as between 1992 and 2017 it seems that the ice cap at the southern hemisphere does tend to melt over time.

The data does not seem exactly apparent from the images collected via Google Earth. For instance, comparing the ice distribution in north America between 1930 and 2020, it is immediately apparent that the ice has receded (even following the evolution via the timeline). However, looking at Antarctica, and perhaps even compensating for what seems to be a lens effect (1983-1984) between 1958 and 2020, it still seems that the overall shape of the Antarctic ice has remained more or less the same.

Some of the same observations have been made in 1997 and the discrepancy between the Arctic and Antarctic ice sheet has been attributed to various procedural issues regarding measurements. One reality of the problem is that whilst the Earth is estimated to be a few billions of years old, the measurements that we have available and are known to be reliable can only reach up to a few centuries at best. Even though the fact that the observable data is lacking does not necessarily mean that humans do not have made an impact, specifically because the time frame of the observable data for both ice quantities and population do match the observability frame.

It could be a hypothesis that moving the population of the northern hemisphere and the population of the southern hemisphere together closer to the equator might have some interesting effects. It could be the case that the Arctic ice cap might recover and gain in mass over time while the Antartic ice cap might start melting at a faster rate. Perhaps, it might be observed in the future that an equilibrium might be met where the ice at both poles might remain constant or decay far less and far less disproportionate. It might be risky given that one cynical outcome could be that both ice caps melt altogether.

The Invisible Hand

In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, vol. II, page 316, Adam Smith says, "By acting according to the dictates of our moral faculties, we necessarily pursue the most effective means for promoting the happiness of mankind.", referring to implicit "powers" that are born just from the dynamics alone due to the separation between private and public interests (in terms of magic, this is known as an engine).

In other words, an individual that acts out of their own best interest, will result in the same individual acting beneficially towards public interest. Assuredly, this could be proven by following the narrative that individuals, even at large and cross-nations, share more-or=less similar contexts. For instance, an individual that hates the smell of gasoline and decides to clean the air through political pressure on the government to take measures and pass legislation, will also end up implicitly cleaning the air for everyone else that shares the same living space. In some ways, the rationale follows the same Rawlsyan principles of the lottery of birth.

The "invisible hand" theory works in economics by design proportional to (state) interventionism. That is, ultimately, random transactions will stabilize the market to a common ground, but if there is external pressure that is artificially generated putting pressure onto the economy, then the expected point of stability will never be reached. This is part of a larger debate on equilibrium and points of market stability given various equations that can model complex systems.

Interestingly Emma Rothshield notes that the "invisible hand" is ironic in the sense that Adam Smith, along with other political figures that would rather see order than chaos, abandons the rational for the sake of consistency of their imagination. Whilst this is true, it must be said that at no point of time is knowledge all-known, such that very complex systems or events that have not been yet documented, sometimes are best described with "loose terminology" such as magic, hinting that there is a truth or that there is a dynamic there, yet it cannot be (even using the word "easily") described. Since the "Economic sentiments" by Emma Rothshield, a lot more is known, and we are now able to mathematically (even) scale economies by using models, such as supply-and-demand, or Pareto efficiency, that have been created by various people attempting to bring order to a place where there was only chaos. That being said, Smith might have just felt the existence of a dynamic but either did not have the background or time to explore it further in order to construct an economic theory out of it; however, relatively-modern economists can describe the dynamic using simple models.

Criticism

One criticism, albeit more of a misunderstanding, is that Smith's "invisible hand" dynamics do not necessarily relate to quality, even as perceived en-masse by large swaths of human populations. In fact, the "invisible hand" cannot be even considered "rational" in terms of market choices as demonstrated by Edward Bernays.

A recent example can be found with The Line a Neom project in Saudi Arabia that originally planned to create a megacity to house 1.5 million people that is always met up-front with criticism by the international scene that ranges either from unfeasible technical aspects of the architecture and up to identity politics. An observer would see the Neom project as a great opportunity, regardless whether the project will eventually fail or not, with regards to the amount of workplaces that will be allocated, as well as the large amount of people that such a megacity could have housed were the original objectives to be met. Having said that, and even to their own detriment, market actors do not always pick the most rational choice and that selection is not necessarily performed strictly as conforming to need, which is the arch-thesis of Edward Bernays that demonstrated that fact.

Some components of the human drive were sensed by Smith even at that time; for instance, Smith was asked what his stance is on speculative markets and Smith considered that volume-trading would be detrimental to the market, thereby somehow suggesting some form of interventionism or protectionism himself in the very same theory. As mentioned before, Smith's ideal capitalism went more along the lines of Marxist theory, specifically the phrase "from each according to their ability, to each according to their need", in that the markets would be small enough to only include direct hand-to-hand transactions rather than economies of scale or speculative trading which do not even fit Smith's capitalist model.

Just like Marx, Smith's capitalist model is just as susceptible to the same kind of impediments that socialist, and later communist systems would suffer from, namely the lesser virtuous traits of human beings such as the ones described by cardinal sins (avarice, gluttony, envy, etc.) that make market players take decisions that are not always congruent with their own best interest, nor with the interest of other fellow players.

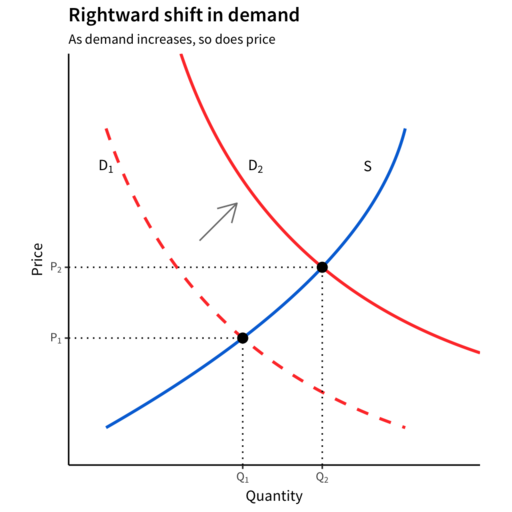

The Supply and Demand Model

The supply-and-demand economic model is a model that suggests that the unit price of items increases as the market demand for the item increases.

The supply-and-demand model is great for explaining the dynamics within small markets that are centered around the direct hand-to-hand exchange of goods but does not cover large-scale economies that are centered on mass-production where the supply-an-demand model does not reflect realities anymore.

Solving the Conundrums Generated by Simplistic Models of Market Price Fluctuations

One of a very classical conundrum is the following: the supply an demand model suggests that higher demand leads to the price per unit being driven up, however in reality bulk prices would suggest that that is not the case, and that high volumetric purchases, counter-intuitively to the supply and demand model, actually drive the price-per-unit down. Furthermore, it is sometimes the case that even the latter effect cannot be observed, even though mass-production is in effect.

In economics, models are used for the exact purpose of describing some state, or some market dynamics, however it must be noted that models are create just like one would create a mathematical model in order to describe and a manipulate a system on its own, and, with that said, with no guarantee that the developed model will necessarily carry to all contexts of a given problem. In other words, the simplistic supply-and-demand model completely collapses on itself when the economy is extended to mass-production, leaving "supply-and-demand" as a great model, but just for very small hand-to-hand and direct-goods exchange economies.

Maybe, in terms of mass-production, the Pareto efficiency model is better suited because it accounts for the fact that scarcity outweighs surplus in terms of relative value.

As an example, if a fisherman has a surplus of fish to trade, then the same fisherman has, as per the theory, lots of other needs that will need to be covered, such that the surplus of fish tends to be less worth than the wares that he cannot acquire. That being said, a fisherman will be happy to exchange large quantities of fish, in order to obtain wares that are outside of his own reach, thereby implicitly driving the price of the unit down.

And yet, how is that not always the case that mass-production drives the unit-price down? One explanation would be governmental intervention in free trade (or the forcing of the invisible hand), where due to taxation, minimal wage and, generally-speaking, cost-pegging results in "artificial" prices that do not accurately reflect the real state of goods distribution, or the state of need and demand, within an economic system.

As an allegory pertaining to physics, "supply-and-demand" economies are to "Newtonian physics", what "the theory of relativity" in physics is to "mass-production economies". That being said, neither are wrong, yet they are both equally right, just that they can be used under different contexts.

For the contact, copyright, license, warranty and privacy terms for the usage of this website please see the contact, license, privacy, copyright.