Table of Contents

Definite Integral

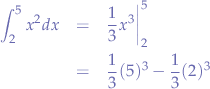

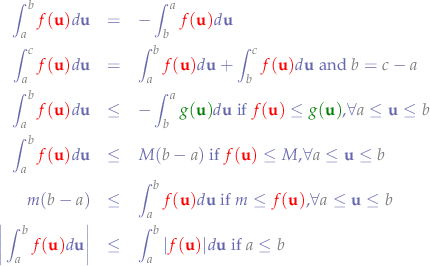

A definite integral is written  and are commonly used to find the area between the graph of a function and the x-axis.

and are commonly used to find the area between the graph of a function and the x-axis.

Example

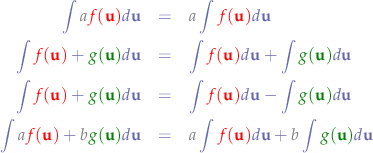

Integrals of Common Functions

are constants,

are constants,  is a variable and

is a variable and  ,

,  are functions.

are functions.

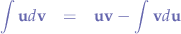

Differentiating Integrals

Differentiation is the symmetric operation of integrating:

![Equations \begin{eqnarray*}

\frac{d}{d{\bf{x}}}\biggr{[}\int {\bf{x}}d{\bf{x}}\biggr{]} &=& {\bf{x}}

\end{eqnarray*}](/lib/exe/fetch.php?media=wiki:latex:/imgc76c87496567ee81c060ec2a427ef25a.png)

Convolution Integral

The convolution of two functions (over the same variable, e.g.  and

and  ) is an operation that produces a separate third function that describes how the first function modifies the second one. Conversely, the resulting function can also be used to describe how the second function modifies the fist function.

) is an operation that produces a separate third function that describes how the first function modifies the second one. Conversely, the resulting function can also be used to describe how the second function modifies the fist function.

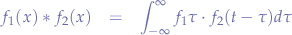

The convolution of two functions is denoted with the  operator and written as:

operator and written as:

where  is a dummy variable.

is a dummy variable.

Here is an example of the convolution of two square pulses  and

and  :

:

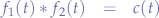

resulting in  .

.

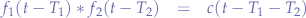

Properties

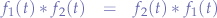

- Commutativity.

- Distributivity.

- Shift

If:

then:

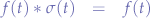

- Convolution with an impulse results in the original function (neutral element).

where  is the unit impulse.

is the unit impulse.

- Width: the convolution of a signal of duration

and a signal of duration

and a signal of duration  will result in a signal of duration

will result in a signal of duration  .

.

Convolution Integral and Circuits

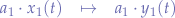

Most electrical circuits are designed to be linear, time-invariant systems (LTI) meaning that the magnitude of a circuit's output signal is a scaled version of the input signal's magnitude. Furthermore, and LTI system that is given two independent signal sources will output the sum of the scaled versions of each signal. Given a function  that causes an

that causes an LTI system to output  , then:

, then:

where  is a multiplicative constant. Given a number of independent signal sources, this gives rise to the concept of signal superposition which allows us to say:

is a multiplicative constant. Given a number of independent signal sources, this gives rise to the concept of signal superposition which allows us to say:

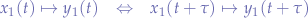

A time-invariant system means it does not matter when the input signal is applied - a specific input signal will always result in the same output signal for a given LTI system. The time-invariance can be expressed as:

where  can be viewed as a time delay when dealing with signals in time (i.e. "time-domain signals"). Indirectly, this concept also signifies than an output signal cannot contain frequency components not inherent in the input signal (causality).

can be viewed as a time delay when dealing with signals in time (i.e. "time-domain signals"). Indirectly, this concept also signifies than an output signal cannot contain frequency components not inherent in the input signal (causality).

The vast majority of circuits are LTI systems, each with a specific impulse response. The "impulse response" of a system is a system's output when its input is fed with an impulse signal - a signal of a brief duration. An example of an "impulse signal" would be a lighting bolt or any form of ESD (electro-static discharge). Any voltage or current that spikes in magnitude for a relatively short period of time may be viewed as an impulse signal. The impulse response of a circuit will always be a time-domain signal and exists because no signal can propagate through a circuit will always be a time-domain signal, and exists because no signal can propagate through a circuit in zero time; each individual electron involved can only move so quickly through each component. Real-world electronic LTI systems exhibit an impulse response that consists of an initial spike in magnitude, followed by an everlasting and ever-decreasing exponential relationship in signal magnitude.

The integral of the impulse response and the input square wave stepped through time can be observed in the image above. The convolution equation is seen as the operation is done with respect to  . In reality, we are taking an input signal, flipping it vertically through the origin and determining whether the what the integral is for each value of

. In reality, we are taking an input signal, flipping it vertically through the origin and determining whether the what the integral is for each value of  which represents in this case a delay through time. Since the output of any

which represents in this case a delay through time. Since the output of any LTI system is non-casual (it cannot exist until the signal that excites the output has seen applied), we must step through time to see how each impulse signal of the input affects the LTI system's impulse response - again, achieved by stepping through  - the "time-delay" dummy variable.

- the "time-delay" dummy variable.

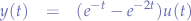

Example

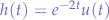

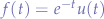

For an LTI system with an impulse response of  , calculate the output

, calculate the output  given the input of

given the input of  .

.

Using the convolution integral, we have to solve:

It only makes sense to integrate between  and

and  because at

because at  the signal is applied and both

the signal is applied and both  and

and  will have zero magnitude at any time

will have zero magnitude at any time  .

.

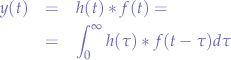

Now we can calculate:

Since  for all

for all  , we can write the output

, we can write the output  as:

as:

which describes the output function for an LTI system with an initial impulse response  when fed the input signal

when fed the input signal  .

.

For the contact, copyright, license, warranty and privacy terms for the usage of this website please see the contact, license, privacy, copyright.